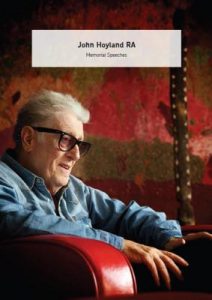

JOHN HOYLAND RA died on the 31 of July 2011 at the age of 76 in London.

As a tribute to one of the finest painters of our time the white8 wants to change the running program showing „GARDEN MOON“ and other works by the artist.

Friendship will survive anyway.

John Hoyland

GARDEN MOON

painting, works on paper

and

Julian Schnabel

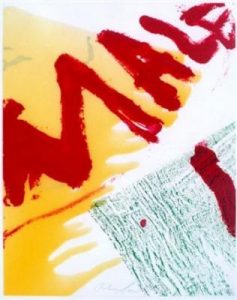

MALFI

works on paper

opening 2 February 6 – 8 pm

duration 30 March 2012

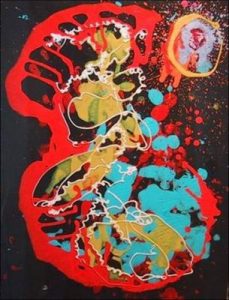

John Hoyland, Untitled, 1992 Thupelo Series (S.A.) Julian Schnabel, Malfi (2), 1998

John Hoyland, Julian Schnabel bei white8 in Wien

Die künstlerische Biografie des britischen Malers und Grafikers John Hoyland (1934—2011) – „who was widely recognised as one of the greatest abstract artists of his time“ (The Guardian, 2011) – steht den Karrieren seiner Künstlerkollegen und -freunde Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Hans Hofmann, Robert Motherwell oder Anthony Caro … in nichts nach: nach seinem Studium an den Royal Academy Schools in London hatte er 1964 die erste Einzelausstellung in der Marlborough Gallery, London, dann folgten Solo shows und Beteiligungen wie: 1967 Whitechapel Art Gallery, London und Waddington Fine Art, Montreal; 1968 documenta 4, Kassel; 1969 X Biennal de São Paulo, Brasilien; 1970 National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; 1979/80 Serpentine Gallery, London; 1982 Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum; 1993 Tate Liverpool; Barbican Gallery, London; 1999 Royal Academy of Arts, London; 2003 Beaux Arts, London; 2006 Tate St Ives; 2010 Yale Centre for British Art … . Sein Leben und Werk war außerdem Gegenstand umfassender Monografien von Autoren wie Mel Gooding (2006) und Andrew Lambirth (2009).

Dennoch blieb dem Briten John Hoyland die offizielle Würdigung des britischen Königshauses, wie sie seine berühmten Landsleute durchwegs erhalten hatten, zu Lebzeiten ebenso verwehrt wie eine große Londoner Retrospektive. Denn Hoyland war immer auch ein Rebell: als Kind einer Arbeiterfamilie (sein Vater war Schneider in Sheffield, seine Mutter förderte mittellos sein künstlerisches Talent) stand er der kommerziellen und auf Ruhm ausgerichteten Kunstwelt stets kritisch gegenüber. Seine Passion galt von Anfang an der „reinen“ Malerei, zunächst insbesondere koloristisch-expressiven Tendenzen, wie sie in Europa z.B. Van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse oder Emil Nolde vertreten hatten. Zugleich war er von Tendenzen zur Abstraktion wie z.B. eines Nicolas de Staël fasziniert, wo es weniger um geometrisch-konstruktive Reduktion des Gegenstandes geht als um die Suche nach einer Position zwischen Figuration, Abstraktion und Emotion. So fühlte er sich auch bei seinem Aufenthalt in den USA in den späten 1960er-Jahren trotz der guten Gesellschaft von New Yorker Künstlern und Kritikern wie Clement Greenberg, Helen Frankenthaler oder Kenneth Noland nicht glücklich in diesem „competitive hothouse of east coast painting“ – und kehrte 1973 schließlich zurück nach England.

Desgleichen sträubte er sich selbst gegen die Etikettierung als „abstrakter Maler“. Vielmehr empfand er sich als ein „painter full stop“ – als ein Künstler, der die Farbpalette wie auch das begrenzte Format traditioneller Tafelmalerei erweitern wollte, indem er, wie etwa Jackson Pollock, die Leinwand von der Staffelei auf den Boden verlegte, um großformatig arbeiten zu können. „Unlike most Americans he poured, and later sculpted, threw and squirted, the paint on to stretch as opposed to loose canvas.“ (The Telegraph, 2012).

Dabei gilt zugleich, was Johannes Rauchenberger bei der Eröffnung der Ausstellung „Painting Poems“ von John Hoyland in der Galerie white8 im Jahr 2007 sagte: „Wie für Newman oder Pollock auf ihre je verschiedene Weise liegt für Hoyland die leitende Obsession seiner Kunst in den Mythen des Ursprungs: Wie Welt entsteht, im Prinzip der Genesis und der Individuation, verbunden mit dem Auftauchen aus dem undifferenzierten Chaos zu einem definierbaren und definitiven Zeichen. Die lebendigen Zeichen und Kreise aus der Acryltube, die erstarrten Formschreibungen in den späten Bildern Hoylands sind Symbole kosmischer Genesis. Sie sind ins Bild gesetzt in ihrer puren expressiven kalligrafischen Funktion.“

Es ist das Verdienst Dagmar Aichholzers, John Hoylands Werk noch zu dessen Lebzeiten in Österreich ins Bewusstsein gerufen zu haben. Allzu oft wird hierzulande vergessen, dass die österreichische Variante einer gestisch-abstrakten Malerei, die ab den 1950er-Jahren als die Avantgarde schlechthin galt und gilt, ohne die großen Vorbilder sowohl aus Frankreich (z.B. Matthieu) als auch aus den USA (Pollock …) und aus England (zu dessen Vertreten eben auch John Hoyland zählt) nicht vorstellbar ist. Von 2003 an bis zu seinem Tode im Vorjahr hat white8 John Hoyland vertreten und sowohl in den Galerien in Villach und Wien als auch auf internationalen Messen gezeigt. Seit seinem Tod ist Hoylands Nachlass nurmehr schwer zugänglich, und doch bemüht sich Dagmar Aichholzer weiterhin um die dem Künstler „am Kontinent“ gebührende Anerkennung – wozu diese Ausstellung einer kleinen Auswahl seiner zwischen 1992 und 2001 entstandenen Werke beitragen soll.

Den Acrylarbeiten John Hoylands werden in dem kleinen „white cube“ der Wiener Dependance von white8 drei 1998 entstandene, mit Kunstharz überarbeitete Serigrafien des US-amerikanischen „Neoexpressionisten“ (und späteren Filmemachers) JulianSchnabel gegenübergestellt. Sie sind Teil einer mit MALFI übertitelten Werkreihe, die Schnabel als Hommage an seinen 1995 in Rom verunglückten Künstler-Freund Paolo Malfi geschaffen hat.

Auch Julian Schnabel kann auf einen kometenhaften Aufstieg zurückblicken, der 1979 mit einer Ausstellung in der Galerie von Mary Boone begann. Ein Jahr zuvor hatte er einige Kisten zerbrochenen Porzellans von der Heilsarmee geholt, die Scherben auf eine Leinwand geklebt, mit Ölfarbe bemalt und sein Markenzeichen erfunden: die Plate Paintings (Teller-Bilder). Was den so gar nicht sensationsscheuen Künstler Schnabel mit John Hoyland verbinden könnte, mag das lebhafte Interesse beider an menschlicher Befindlichkeit sein – bei Schnabel einer, „die das Subjekt als verloren zwischen dem Vorher und dem Danach begreift, wo eigentlich Gegenwart sein müsste“. So schreibt Rose-Maria Gropp (FAZ 2004) weiter: „Die Dekonstruktion der Schönheit, ohne die Schönheit zu zerstören, ohne ihr den Reiz auszutreiben, das ist Schnabels Domäne: Er betreibt als Maler jene mise en abime, die ein Bild hinter dem vorigen und dem nächsten Bild herjagt, um nur ja das Ende zu vermeiden, die Akzeptanz der Vergänglichkeit. Diese Arbeit gegen die Zeitlichkeit okkupiert Raum, als Dimension des Ausweichens vor der Zeit.“

Lucas Gehrmann

Jeremy Hoyland

On behalf of Beverley and the whole family I would like to welcome all of you to today’s celebration and memorial and to say just a few words, important ones though that should be said.

I am not here as a painter, but as John’s son and also, simply as an informal member of the public who for 53 years knew a fighter, a visionary, a man of extraordinary commitment, a person who overcame doubt, disappointment, criticism with matchless humour, truly ascerbic wit, fierce determination and sheer intellectual force.

Dad was by no means perfect, and made many mistakes, but he had total integrity with regard to his painting.

He refused lucrative commissions when he was down to his last buck and was entirely willing to jeopardize his commercial prospects through outspoken comment. He never ever painted for money, only for passion, out of belief and a burning desire to illuminate the inner and external world, to bring people to their senses or at the very least to create an escape into their imagination.

In the years to come his work should not be hidden. It deserves to be seen for no other reason than on its own merits.

He is gone now and sadly so too is his beloved mother, who died on Sunday. If it were not for grandma, dad would quite possibly not even have been an artist. They had a special bond; when dad died, grandma’s heart was broken, she should have been here today, but last Saturday, she told Jackie and I in typical Yorkshire fashion, having made her decision, “no more”, “end of story”, refused any more food and decided to join her son.

Today though is about John Hoyland the artist. The man is gone, besides leaving his wonderful wife Beverley and a dancer, musician and a teacher between his grandchildren; he is one of the fortunate few who can live on through the light of his artist’s legacy. How bright that light is, how many souls it will stir, how many rooms it will illuminate, is no longer down to him but to those of us who are left. There are many wonderful artists and friends here who admired his work all these years.

Each of us has the chance to create value in our own lives but as John is no more, I would ask that for those of you who really knew John and believe in the incandescent value of his work, that you help our family make that work achieve the standing and crucially the visibility it deserves in a world of populist trash culture and often selfish, inward looking superficial values.

We are deeply grateful for all the help that is already forthcoming and has been offered.

Heart I noticed this morning is “he” with “art”; the best art puts heart in to the lives of many and God knows the world needs more of that.

Thank you and on behalf of John’s widow Beverley and all the family, again welcome.

Sir Philip Dowson PPRA

John’s association with the Royal Academy began over half a century ago, when he was a student in the schools, having first studied art in his home town of Sheffield.

Sir Henry Rushbury was then Keeper. John greatly admired him, because he maintained the reputation of the Schools as a centre of draftsmanship as well as granting students the freedom to pursue their own stars – in which in John’s case included the avant-garde.

John duly showed his abstract work for his diploma. However Sir Charles Wheeler – then President – asked for it to be removed from the show. John’s actual diploma was only awarded on the strength of his early figurative work, executed whilst at the schools. So he graduated already having left his mark!

Apart from John’s career as a great painter, he also had one as a teacher – spanning five decades. He was finally appointed professor of painting at the Royal Academy Schools in 1999, a position which he held for 10 years.

John loved the Academy, and particularly the schools. He had a strongly held belief in their ethos and took great pride in helping them and participating in raising funds for their support.

Behind all this though, John had a very sharp intellect as well as an acerbic wit. He also wrote with clarity and weight about art. His was a rare, rare gift. Coupled with a life-long passion, his vibrant work carries with it a joyous and wonderful legacy that will endure.

We shall of course all sorely miss him. But today we celebrate his life, and John, after all, loved celebration!

Tony Caro

John Hoyland was a very fine painter. His best pictures stand alongside those of the post-war abstract artists, giants like Rothko, Motherwell, Noland and Frankenthaler. And I believe history will confirm this judgement.

But rather than dwell on this work I’d like to talk about John as I knew him. Together will Paul Huxley he had been accepted for the RA Schools but I don’t think our studentships quite overlapped. My earliest recollection of John was when we were invited to see his work at this home in Kingston-on-Thames. That must have been in the early 60’s.

Later he moved to Oppidans Road in Primrose Hill. There he literally painted himself into a corner – every room was filled with pictures stretched and stored, so much so that the hallway and front door entrance were blocked so I had to climb through the ground floor window.

I got to know John well on the trip we made together to South America in 1969. We had been selected by the British Council under Lillian Someville to show in the Sao Paulo Biennale. Travelling together for 2 or 3 weeks we became fast friends.

I encountered in John a person of great integrity, thoroughly decent, generous, honest, and down to earth. His upbeat fun-loving exterior masked a seriousness, almost an idealism, about his work and his life.

He had a wicked sense of humour and he brought a cheerfulness to any room he entered. He had a great capacity for friendship and unshakeable loyalty. It was evident that he had deep affection for Beverly, for his mother who has died in the last week, and for his son Jeremy. He loved life.

In what he did there were never ulterior or hidden motives. What you saw is what you got, but underlying it was a depth of feeling, of belief in the worthwhileness of life.

We all have precious memories of John. He was a big man. With his loss we have had some colour taken from our lives. This memorial today is a commemoration of his life. It was a life lived to the full and we are all of us richer for having known him.

Chris Yetton

I first met John Hoyland in 1963 and knew him best throughout the 60s when we were both teaching at Chelsea School of Art. His total dedication to being an artist combined with an exuberant light-heartedness was one of the things that made working at Chelsea so much fun. It was like being a member of the best club in the world. My overriding emotion when walking round his great 1967 Whitechapel show was of feeling lucky to be alive.

I was a young naive art historian trying to understand contemporary art, six years his junior and light years behind him in the knowledge of painting. He never gave the slightest sign of being aware of the gap between us. He was so warm and generous to me and we spent a lot of time talking about art and everything else.

We swapped stories about our first visits to New York – he had gone there in 1964, a year before me. He talked about arguing with Greenberg and how welcoming Barnet Newman, Motherwell, Helen Frankenthaler and Jules Olitski were. He also talked about the great jazz players he had heard there – and met. It always struck me that he was a lot like them.

All artists are on their own in relation to their work but John embodied that existential aloneness rather in the manner of a great jazz improviser. He also had their caustic dry wit and hatred of bullshit. He went to New York as to a ‘cutting contest’, intent on showing the painters he reckoned the best of his time that he could outpaint them.

I will really miss him.

A year ago I spent a week with him at Yale on the occasion of the donation of the Sam and Gabriel Lurie Collection to the Yale Center for British Art. We talked a lot about the 60s and about Pat Caulfield and Ian Stephenson, who featured strongly with him in the Lurie Collection and who had also been there at Chelsea. He was physically frail and I realised that the strength and power – often associated in the 60s with his imposing physical presence – were in reality of the spirit and still there as strongly as ever.

The physical quality I now recall so vividly is his lovely Yorkshire voice, with an added transatlantic drawl, in which he told his marvellous stories.

Angus Trumble

On behalf of the director, Amy Meyers, and the whole staff of the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, I come this morning as an emissary to pay our tribute to John Hoyland. We mourn the loss of such a distinguished Royal Academician, and, of course, we pay our respects to Beverley, to Jeremy, and to their family and many friends and colleagues.

Last autumn John’s work was seen in abundance at Yale thanks to the generosity of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Lurie, who have for decades supported John, and acquired a great deal of his work. We were delighted not only that John and Beverley were with us then, and gave so generously of their time, above all for our students—he really was a trooper—but also that John was able to know and derive satisfaction from the decision reached by Mr. and Mrs. Lurie to present to Yale their entire collection of his work.

John has been a presence in the United States since the mid-1960s when in New York he attained the recognition of the powerful critic Clement Greenberg—not, I think, an easy feat because with that recognition Greenberg was famously parsimonious—but thanks to this remarkable gift henceforth John will remain powerfully present with us for as long as earthly things endure. And for that we give hearty thanks.

As the Rector pointed out in the beginning, light is at the heart of the Judaeo-Christian tradition, and there can be no color without light. If poetry is music set to words, as a colleague of mine suggested lately, then great paintings may be, can be, poems wrought by color. No doubt they are many other things too, but John’s work surely brings us in that direction. The death of a major painter, and a colorist as dazzling as he was, inevitably makes us wonder where that light came from, and what it means for talented individuals to harness and share it for the benefit of all who care to look.

Though John has gone, the colors remain, reflecting the light—the sunlight of the Mediterranean and of tropical places: Jamaica and the waters of the Caribbean; the lush green hills of Bali; even the ocean beaches of southeastern Australia. But in a larger sense John’s work, his legacy, surely hints at what in this great parish church we call light perpetual. May it shine upon him.

Mel Gooding

I want speak of John Hoyland the artist. In his beautiful graveside eulogy to his dear friend Patrick Caulfield, John remarked that more than anyone he had ever known, Patrick had been his own man, true to himself. Exactly the same could said of John in every respect: I would say that John was from first to last his own artist. He realised his vocation early in his life, and forever after he made the work he wanted to make, in the way he wanted to make it. He was an original genius: which is to say he was deeply knowledgeable of the definitive originality of the other great artists he admired, and that in his own work he was always in creative conversation – or contention – with them. He was an artist of grand ambition: ambition fulfilled.

It is possible now to see John Hoyland’s one-man exhibition at the Whitechapel in 1967 as a defining moment in British painting. In his early thirties, he had produced an astonishing body of work: ‘brilliant colour, full, unmixed… reds, greens and oranges’ deployed with an absolute formal clarity in radiant theatres of colour. The intelligence, originality and imaginative grandeur of the paintings in that show established him without question as one of the two or three best abstract painters of his generation anywhere in the world. The magisterial impersonality of those paintings, the authority of their objectivity, derives from a distilled energy of both thought and emotion, and the absolute concentration of the contemplative, the meditative seer forgetful of circumstance.

In the great paintings of the later ‘70s, strong forms, brilliant colours and complex textures were structured into compositions of a pulsating visual music – with now a rich consonant chord, now a dissonance, now a harmony, now a discord. In Hoyland’s second retrospective, at the Serpentine Gallery in 1979, these paintings succeeded each other in sonorous grandeur, like the movements of a great symphony.

It was clear to those who saw the Serpentine exhibition that Hoyland was not only a colourist of genius, but a master builder, an engineer of ‘great machines’. That was the term Constable used to describe the large-scale paintings he worked up for presentation at the Royal Academy: majestic orchestrations of the effects of nature into symphonic topographies. And John’s paintings of the 70s might also properly remind us of Turner’s tumultuous analogies, his awesome painterly enactments of atmospheric natural process. Hoyland’s painting in the late ‘70s and after drew confidently on the English tradition of the landscape sublime. (It was Robert Motherwell who once declared to a surprised Hoyland: ‘John, you could be the next Turner.’)

Some critics found the uninhibited exuberance of Hoyland’s later painting, its superabundance of visual effects and its technical extremism overwhelming. But those who loved this work were exhilarated by its spectacular diversity, by the thrilling sense of an imperious imagination, an impulse to fantasy that took him again and again to the very extreme of what painting could do. His work refused to settle into any kind of academism, refused to conform to canons of taste or restraint; it was unconstrained by prescriptive definitions of style. The fantasia of his late paintings was as fecund as Miro’s.

When we see a third great retrospective the full measure of his achievement will be revealed for us to celebrate: for John committed himself to a life in painting at a time when its validity and viability as a medium for a truly modern art was called into question. In an age of anxiety for painters, in which his contemporaries were haunted by the questions of what to paint, how to paint, or whether to paint at all, Hoyland suffered no doubt about his vocation: he painted because that was his chosen means to the poetic expression of a life. And what, in his rich and free-spirited life, fired his painterly imagination? Here is that marvellous list he made of what he considered to be the inspirations and subjects of his art:

‘Shields, masks, tools, artefacts, mirrors, Avebury Circle, swimming underwater, snorkling, views from planes, volcanoes, mountains, waterfalls, rocks, graffiti, stains, damp walls, cracked pavements, puddles, the cosmos inside the human body, food, drink, being drunk, sex, music, dancing, relentless rhythm, the Caribbean, the tropical light, the northern light, the oceanic light. Primitive art, peasant art, Indian art, Japanese and Chinese art, musical instruments, drums, jazz, the spectacle of sport, the colour of sport, magic realism, Borges, the metaphysical, dawn, sunsets, fish eyes, trees, flowers, seas, atolls. The Book of Imaginary Beings, the Dictionary of Angels, heraldry, North American Indian blankets, Rio de Janeiro, Montego Bay!’

I would add to that list: Chinese poetry, Zen, domestic pottery, driving cars, birds and reptiles, the sun, moon and the stars.

We should thank our lucky stars to have been offered such worlds to imagine; such invitations to dream.

Allen Jones RA

As we all know, John had a strong physical presence, an Alpha male who did not like to be bested in art or life.

Once I threw a party for the American Pop artist, Mel Ramos, whose works were stylistically a million miles from John’s, and asked afterwards if John had spoken to him – “Only to tell me that he was the better artist!” was the reply.

Another time, when his closest friend, Pat Caulfield, had an exhibition of large, magnificent paintings, John could only manage to deliver a compliment by punching him at the same time on the arm.

More recently, Damian Hirst had asked to meet with Caulfield who, ever reticent, had asked John to go with him to the restaurant for moral support. John told me later that after the meal he took Hirst aside and asked him if he realised that he could throw him through the window if he wanted to!

We first met half a century ago. I remember seeing his pictures in the influential “Situation” exhibition of 1961 with Bernard Cohen and Dick Smith being in the same show.

There is an affectionate image from that time of John sitting on a bunk bed with his young son, Jeremy, below him. Lord Snowdon’s photograph was in a book called “Private View”, which was a cross section of the avant garde at the time.

John’s first wife – (Jeremy’s mother) – was a tall, curvaceous, striking blonde Viking – well, she was from Finland actually.

Later, after he and Iri were divorced, he looked forward to seeing his son, and on one occasion took him to the cinema. He was tickled pink when an old man sitting behind them started to hit him on the head with a rolled up newspaper, shouting

“You ought to be ashamed of yourself”, –

John had put his arm around Jeremy’s shoulder.

He was frightened of dogs! Once, while walking on the Common, an Alsatian made a beeline for him. Waiting until it was nearly upon him he caught it under the jaw with a well –aimed kick – End of Threat!

More recently John was visiting Helen Frankenthaler who left him alone for a while with her large dog. John told me that when it came over to see him he grabbed it by the muzzle with one hand and punched it smartly on the side of the head with the other. Helen could not understand why the dog was so quiet for the rest of the evening!

For over 30 years we were neighbours in the same building in Charterhouse Square. I had the top 2 floors of our building whilst John had the floor below – it was the only situation in which John had to admit that I was on top…

In the early 60’s America happened for both of us. Bryan Robertson was responsible for introductions to the Abstract Expressionists, our American heroes.

John was never over-awed by New York. When going to hang his exhibition at André Emerich on Madison Avenue he was asked if he should perhaps wait for Clement Greeenburg who usually hung the exhibitions. John declined and hung his own show.

Later Greenburg told him he had left out the best picture – incidentally the only one that sold from the show.

In later years the miracle that happened to John was Beverley, whom he later married. He was so proud of her. He told me that once, while driving with Beverley in downtown Kingston, Jamaica, the local lads threw rocks at the car because they could see him inside with their very own “Miss Jamaica”.

On hearing of John’s death I sat in contemplation and started jotting down these notes. By chance the “Four Last Songs” of Strauss were playing on the radio, a fitting culmination to that artist’s career. It reminded me of the two last paintings by John that I had the pleasure of hanging in that year’s Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy.

These large, majestic works flanked the doorway at one end of the gallery and I surrounded them with pictures by friends and fellow artists who in some way he had inspired. Little did I realise that these would also be a summation of his career.

He was a master of the creative art of painting by hand, a true champion of the ideas laid down by the great American painters of the generation that immediately preceded us.

I will miss him, his wife, and family, and friends will miss him, and so will the Royal Academy.

Ian Ritchie

John invited me last February to write the essay for his last show “Mysteries” at Beaux Arts.

I wrote:

They are fugitive images that evoke worlds other than the physical ones that we have been taught exist. They are deep.

When I look at his work, I feel that I am privately interviewing John, not with questions and words, but soul to soul – a language of the spirit.

His latest paintings reveal a defiant journey between his imagination and skill as a painter with the physical pain wracking his body. The challenge of the infinite – the void – at the centre of many of his late works – is his confrontation with eternity.

He was a painter’s painter, an audacious warrior whose colours will resonate forever. He recalled in word and paint, his heroes – Van Gogh and Miro, and his friends, Terry Frost and Patrick Caulfield.

John was free of media and fashion. He was his own man. In 2010 He wrote:

A Brit Art Lament

“I think I must be slipping

Not had a gimmick all week

By the Tate I’ve been abandoned

Can’t get a wink of sleep.

What happened to my stunting

I did have one or two

I think I’ll ring up Saatchi

He’s good for quite a few.”

He was flying in his final years into the metaphysical domain. “You choose structure, but colour is like love, it chooses you.” he said. From among many quotes in his notebooks, I quote one by Plato:

“Music is a moral law. It gives soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, a charm to sadness, gaiety and life to everything.”

John loved music, reading and writing poetry – here’s one.

Dreaming While Awake by John in 2003

Dreams wander on

Winding far

The bird’s path

Hangs the sky with stars

Leaving no trace

Night after night

The moon

Dawn after dawn

The sun.

His colours became his thought waves, and his vibrant triumph can be felt in his last paintings. John has left behind untold quantities of energy and a voice somewhat unheard. His genius and spirit will live on while we discuss and enjoy his work.

John was always journeying, never arriving, always performing, and he only stopped when they put him in a box.

I consider myself extremely fortunate to have known John. We became soul mates and we revelled in the madness of the discovery.

Jamaica is John’s spiritual home.

Its vitality, music, heat, sea and colours were central to his life. He could not stop talking about them, nor resist sending expressive postcards.

Beverley,

Your particular sensitivity and understanding of John’s need to be alone a lot of the time, along with your humour, style and beauty has been such a rock in his life. You generously gave me private time with John, and in his final hours – a special moment to say farewell.

John’s legacy is the power and value of imagination and his work will inspire others for generations to come.

When thinking about this tribute, I wrote,

“The unteachable human spirit aspiring to the unreachable.”

This was his art.

‘I paint, therefore I am’ could be his epitaph.

Jeremy Hoyland (Ed.): John Hoyland RA. Memory Speeches.